“It was all over. Brazil had won its first World Soccer Cup, a 30-centimeter-high statuette of a woman which was offered in 1930 and is now the most envied trophy in the world’s biggest international sport. Brazil itself went wild,” John Mulliken wrote in a 1958 Sports Illustrated article.

The final game (Brazil 5 v. Sweden 2) of the 1958 World Cup was played on June 29 of that year. Courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

When General Charles de Gaulle famously said in 1963, “Brazil, ce n’est pas un pays sérieux (Brazil, that is not a serious country),” he reflected common foreign perceptions about Brazil’s adolescence as a country. Yet the French leader, like many observers, overlooked on important detail about Brazil: By 1963, Brazil was serious about soccer.

From 1938, when it first made its mark in international soccer, to the 1970s, Brazil experienced a golden age in the sport. The national team’s success culminated in the 1970 International Federation of Football Association (FIFA) World Cup, held in Mexico, when Brazil became the only country to win the Cup three times. From the 1930s to the 1970s, Brazilian soccer strengthened Brazil’s national identity. Brazil’s distinctive form of soccer excellence provided a counterpoint to the standard view of Brazil as a backward, underdeveloped nation. Yet the positive image of Brazil built on its soccer strength still faced contradictions that held the country’s reputation, and later its development, back; Outside coverage and analysis never fully stopped portraying Brazilian soccer as one more example of the country’s stunted development—as a raw asset that was less than fully formed.

The Rise of Brazilian Soccer

When football first arrived in Brazil in 1894, the British sport was an elitist game. It was largely restricted to private, urban, amateur clubs, and the players were mostly European-born. Over time, however, as the sport spread to suburban areas inhabited by people of lower-class backgrounds, the pelada [informal] culture emerged. Young, poor, black Brazilians played spontaneous pick-up matches on beaches and open fields. An important breakthrough came in 1923 when Rio de Janeiro’s Vasco de Gama Club, founded in 1898 by affluent Portuguese bankers, allowed poor blacks and mulattos to join and went on to win the city championship that year.

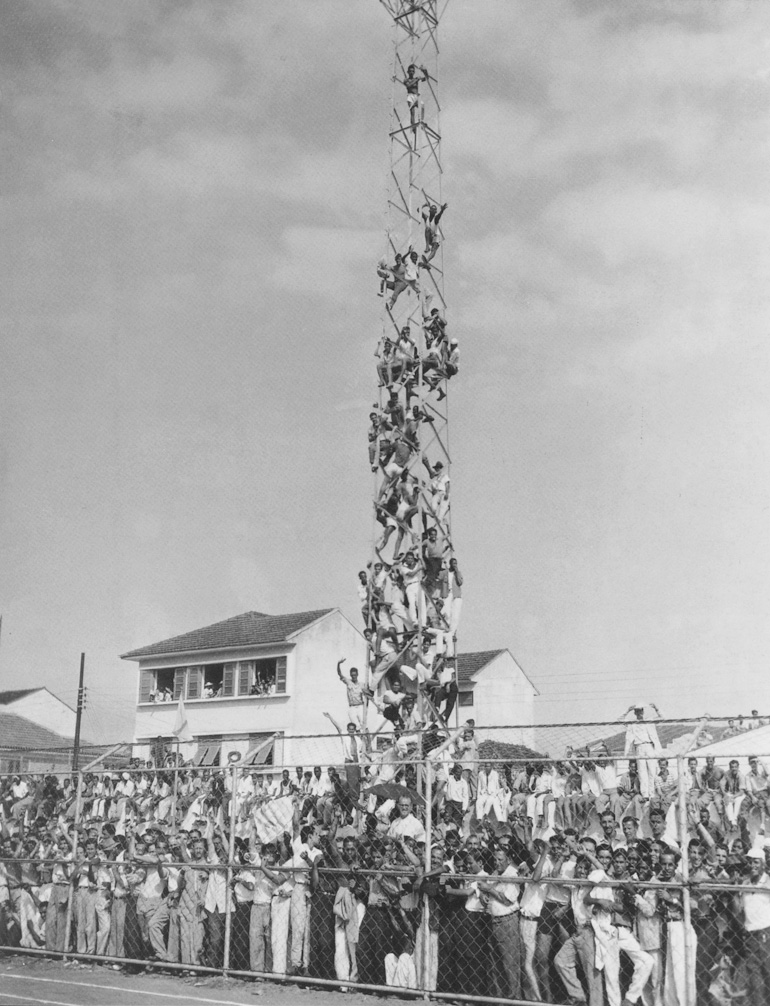

This image of fans going to extreme lengths to watch a game in November 1951 illustrates the widespread appeal soccer held by the 1950s. Courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

The quadrennial World Cup, a form of “mock war,” allowed Brazil to assert its dominance. The “beautiful game,” as it was called by the British, with its unique emphasis on footwork, dribbling, natural and improvised rhythmic moves, became a national asset. Brazil hosted the 1950 World Cup in Rio’s new stadium, the Maracana, the world’s largest at the time.

The ’58 World Cup was a national experience. One Brazilian journalist wrote in the newspaper Ultima Hora of the new national pride, the sense that Brazil no longer had to consider itself inferior to the other countries it met in competition, not only because of the way the team played the game but because of the way the players behaved:

Here in Brazil, at the same time, every one of us wanted to sit on the curb and cry. Every grown man lost the shame to mourn his own happiness. Shame would be to stay dry, parched like a tap from the Zona Sul. And, now, with the arrival of the immortal team, the tears fall anew. We admit that this “scratch” (a term of endearment for the Brazilian national team) deserves them. It deserves them for everything: not just for the soccer, which was the most beautiful mortal eyes have ever seen, but also for its marvelous disciplinary index. Until this championship, the Brazilian was judged a boor, born and bred. He would hear English and envy it. He thought the Englishman the finest, the most sober type of man, with an unspeakable politeness and ceremony … [in this championship] the following became clear: the Englishman, as we conceived of him, does not exist. The only Englishman that appeared, in the World Cup, was the Brazilian. For these reasons, we will not be ashamed … we are going to sit on the curb and cry. Because it is a joy to be Brazilian, friends (Rodrigues, 62)!

Soccer as Export

Although, in many ways, soccer helped to elevate Brazil in the second half of the twentieth century, U.S. and other foreign coverage of the sport tended to mirror historic patterns in coverage of Brazil’s culture, economy, and politics. It was regarded as yet one more of the country’s natural resources: Soccer strength, like other resources, had the potential to help empower the nation, yet it served to keep Brazil under the thumb of outside powers once it came to be exploited, as had brazilwood, coffee, and sugar at other points in the country’s history. Eventually, as soccer developed in Brazil, foreign businesses from the more modernized European nations and the United States took advantage of Brazilian soccer much as they had with its natural resources. And, as with those resources, the outside powers gradually depleted and polluted Brazil’s natural soccer strengths.

Fans commemorate a Brazilian goal against Bulgaria from the 1966 Cup. Courtesy of Ultima Hora, in the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

Foreign newspaper and magazine articles have repeatedly used certain tropes and themes to characterize Brazil and its people as backward, under-developed, childlike, poor, and corrupt. Descriptions of futebol—the distinct style of play that made Brazil great—often revealed a similar tone of superiority. While futebol, in some ways, still provided contrast with other lagging industries as something at which Brazil excelled, it often inspired depictions that made it seem wild and unstructured.

Tomás Mazzoni, an Argentinean journalist writing in 1949, vividly described Brazilian soccer’s wild, improvisational rhythm and its sharp divergence from the European style:

For the Englishman, football is athletic exercise; for the Brazilians it’s a game. The Englishman considers a player that dribbles three times in succession is a nuisance; the Brazilian considers him a virtuoso. English football, well-played, is like a symphonic orchestra; well-played, Brazilian football is like an extremely hot jazz band. The English player thinks; the Brazilian improvises (Hamilton 188).

Mulliken’s 1958 Sports Illustrated article, released after Brazil won the World Cup for the first time, repeated this condescending characterization:

The artistic, dazzling Brazilians, who do not like hard-tackling type of defense, which characterizes European soccer, were expected to be troubled by the vigor of the straight-shooting Swedes (Mulliken).

According to these writers, Brazilian soccer is artistic, natural, and dance-like, but also wild, vulnerable, and disorganized in comparison to the structured style of European play. Such descriptions carried on into the 1970s, with another Sports Illustrated article said the team played “with the fluid rhythm of a conga dancer.”

Similarly, journalists and analysts highlighted Brazil’s lack of infrastructure and backwardness by portraying soccer as a poor man’s game, wracked with disorganization and corruption. The Brazilian soccer clubs, run by the corrupt cartolas, existed as private, amateur institutions. Because the private “non-profit” clubs were not subject to public scrutiny, they often fell into corrupt practices.

The Decline of the Game

Not only was Brazilian soccer portrayed as a natural resource by the foreign press, but increasingly after the ’58 World Cup, foreigners took concrete steps to commercialize and exploit that natural resource. “Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of sugar, coffee, and footballers,” Alex Bellos writes in his 2002 analysis of the history of the game, Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life. “I began to see the country as a big estate where the agricultural product is ‘futebol.’ The country is a sporting monoculture. And football mirrors the old hierarchies.”

In extracting the valuable resources of Brazilian soccer, the players were the first to go. American and European teams began to raid Brazil’s national talent, turning players into exports. Every time a rising star became a favorite, he was sold off to Europe or the United States, joining a team there. Perhaps the most significant example, Pelé, signed $4.7 million contract to play for the New York Cosmos in 1975, shortly after leading his national team to victory in the 1970 World Cup.

The structure and system of Brazilian soccer were next. Business-oriented foreigners, trying to commercialize and professionalize what they viewed as Brazil’s disorganized, corrupt, and amateur sport, seized opportunities to tap the sport’s profit potential. In 1998, when the Brazilian national team returned home after losing to France, fans were waiting with Brazilian flags in which the Nike swoosh replaced the motto “Order and Progress.” The Brazilian Football Confederation had entered into a deal with Nike that, in essence, sold its team. The Nike flag was emblematic of the foreign takeover of Brazilian soccer.

Pelé

Pelé’s unconventional style of play fit with the international public’s view of Brazilian soccer as backwards, but it proved critical to his team’s 1958 victory and helped catapult him to superstardom. From the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

The experience of the most outstanding Brazilian player in history, Pelé, is a microcosm for the fate of Brazilian futebol. Raised in the streets of a São Paulo favela, he was 17 years old when he played in the 1958 World Cup. His back-heel moves and famous bicycle kick were seen as unconventional and backward. Even his name reinforced this image—”Its simplicity and childishness reflects the purity of his genius,” Bellos writes.

In 1975, in the Hunt Room of the 21 Club in Manhattan, Pelé signed a multi-million dollar contract with Warner Communications, Inc. to play for the New York Cosmos. Pelé became a brand, an international reference point, and the most registered name after Coca-Cola in 1970s Europe. His is a quintessential rags-to-riches story, but it is also the story of how globalization and commercialization took over what had originally been an inspiring story of personal success.

Over the course of Brazil’s history, more developed countries have tended to view Brazil as a younger version of themselves, and have assumed that Brazil should follow their models of progress and development. Although soccer started out as a British import, it quickly took on a distinctly Brazilian quality. It was that quality—the open, improvisational nature of futebol—that propelled Brazil to its greatest success on the field. Along with that success, however, came the growing influence of more developed countries and outside businesses that sought to develop the “natural resource” of soccer and eventually deplete it.

The golden age of Brazilian soccer came to a close, and the game—now in disarray—struggles to live up to past expectations. “The dream has ended, and it’s a shame, because it was a beautiful dream,” a New York Times article announced following Brazil’s defeat in the 1982 World Cup. In the end, though, Brazil’s success from 1950 to 1970 and the international recognition of that success cannot be undone or forgotten; it remains a source of national pride as an example of what Brazil is capable of accomplishing on its own terms.

Further Reading

- Janet Lever’s Soccer Madness addresses the role of soccer, Brazil’s primary mass sport, in the country’s development: its role in social control, class dynamics, and national infrastructure.

Sources

- Bellos, Alex. Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life. New York: Bloomsbury, 2002.

- Hamilton, Aidan. An Entirely Different Game: The British Influence on Brazilian Football. Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1998.

- Hoge, Warren. “Brazil Mourns Its Fallen Soccer Team.” New York Times (8 July, 1982).

- Levine, Robert M. “Sport and Society: The Case of Brazilian Futebol.” Luso-Brazilian Review 17:2 (Winter 1980).

- Mulliken, John. “The Samba No One Could Match.” Sports Illustrated (July 7, 1958).